The California Clean Cars and Clean Air Act: What New York State Needs to Save Us from the Climate Crisis? An Environmental Report on the California Carbon Budget

The climate vote in California was not very well received. The Clean Cars and Clean Air Act was intended to tackle two of the biggest drivers of dirty air in the state: wildfires and car exhaust. (California has some of the worst air quality in the US: Of the 30 counties with the worst air quality nationwide in 2020, 29 were in the Golden State, a recent analysis found.) Prop 30 would have increased taxes on residents making more than $2 million by 1.75 percent, with the revenue—about $3.5 billion to $5 billion annually—supporting the transition to zero-emission vehicles by providing subsidies for car buyers and building charging stations. It would have also funded wildfire risk reduction programs. The measure saw support from environmental advocates, firefighters, the California Democratic Party, and rideshare company Lyft, which backed it to the tune of $45 million.

First up, New York: Proposal 1, the “Clean Water, Clean Air, and Green Jobs Environmental Bond Act,” is a wide-ranging initiative that will supply more than $4 billion in funding for projects related to “the environment, natural resources, water infrastructure, and climate change mitigation,” paid for through New York’s sale of bonds. Wetlands, solar and wind installations and street trees are some of the things it will help with. New York is one of the first states in the country to require all of its school buses to be zero-emission vehicles because of the $500 million in funding earmarked for electric school buses.

The measure also requires that at least 35 percent of the money benefits “disadvantaged communities,” as defined by an independent advisory committee. New York isn’t alone on this front; in 2021, Joe Biden issued an executive order declaring that disadvantaged communities would receive at least 40 percent of climate-related benefits enacted by his administration, although it’s unclear how such communities would qualify.

Not surprisingly, Democratic governor Kathy Hochul (who handily won reelection) and environmental groups supported Prop 1. The New York State Conservative Party opposed it, arguing that New York doesn’t need to borrow more money. 71 percent of votes were counted by Wednesday afternoon, with 69 percent of New Yorkers favoring it. Bond sales could reportedly begin as early as next year.

The Nature Conservancy’s policy and strategy director, Jessica Ottney Mahar, said New York voters deserve a shout-out for their overwhelming support of a once-in-a- generation bond measure that protects and restores the natural resources we all depend on. “This is a major victory for people and for the environment.”

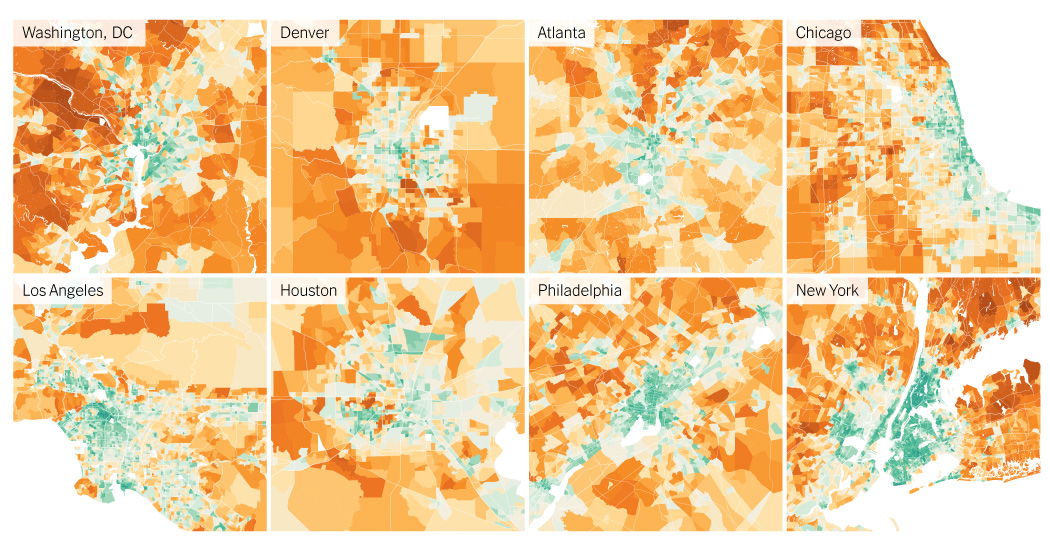

For many cities, then, the most effective climate policy they can pursue is to build more homes in low-emissions neighborhoods, so that more people have the option of living someplace where they don’t need to drive as much. Not everyone will want to move to denser parts of San Francisco or Berkeley, of course. But the fact that it’s so expensive in those neighborhoods suggests that demand is a lot higher than supply at the moment.

The new research offers some guidance for how local governments could pursue more climate-friendly housing policy, said Chris Jones, director of the CoolClimate Network at UC Berkeley, which developed the methodology behind the data set. For one, not every city needs massive new skyscrapers. Even some smaller town centers in suburban neighborhoods can be quite sustainable and might be good places for more housing.